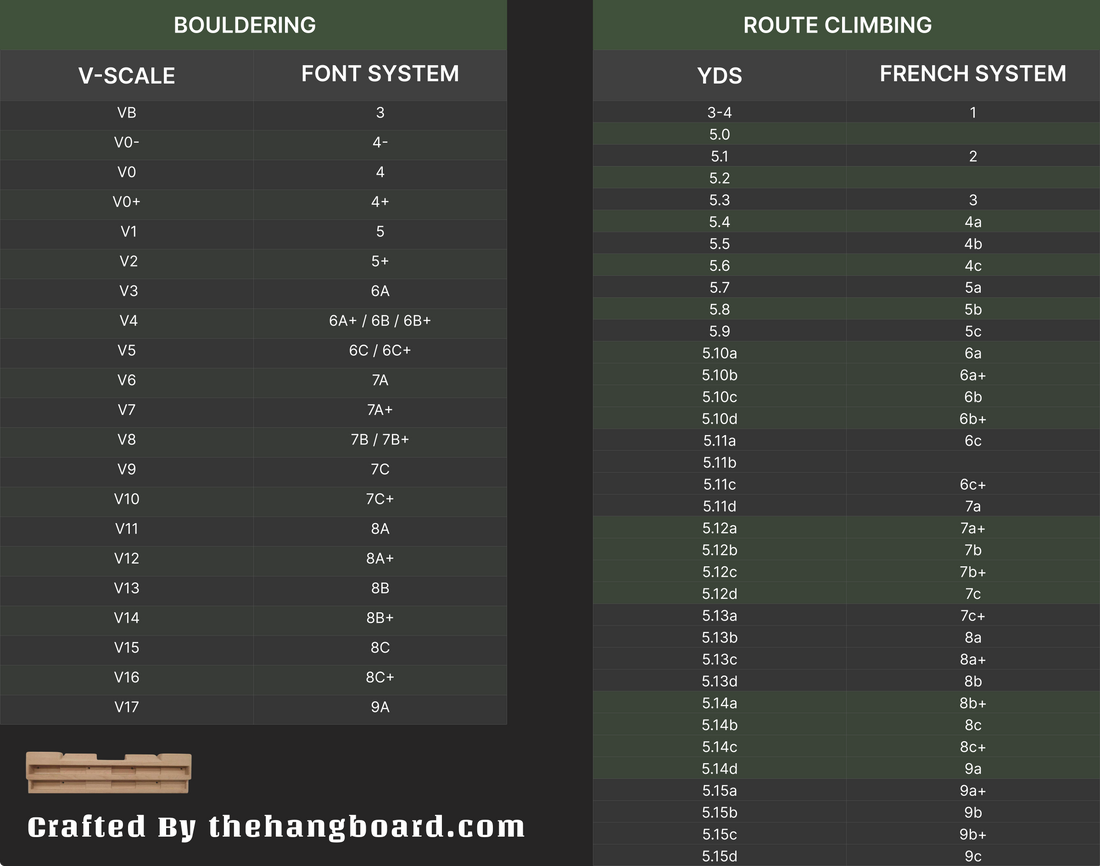

Rock climbing is a diverse sport with many different disciplines. Each discipline or style has nuances that make it unique, including climbing grades. Climbing grades are numbers, letters, and symbols that are designed to represent the proposed difficulty of a certain climb. Climbing grades range from easy to hard and vary based on geographic location, climbing discipline, and whether you are indoors or outdoors.

To keep things simple when thinking about climbing grades, it’s convenient to think about the styles of rock climbing with one important distinction– the usage of a rope or not.

Roped climbing, or route climbing like sport and traditional climbing, has a unique grading system from unroped climbing like bouldering. In this article, we will break down the different grade systems, discuss where they came from, and share some climbing grade conversion charts.

Route Climbing Grading Systems

The two most prominent forms of route climbing are traditional (also known as trad) and sport climbing. Yes, there is aid climbing also, but considering the complexity of aid climbing grades and the popularity of the other two styles, we want to focus on trad and sport.

French Scale

The current French grading scale for rock climbing was developed from the old International Union of Alpine Associations (UIAA) grading system. The UIAA system, which was popularized in the 1960s as the “Welzenbach Scale,” was composed of Roman numerals from I to VI followed by either a “+” or “-.”

Later, in the 1980s, French climbing guides presented the French scale, which replaced the Roman numerals with Arabic numerals. Climbs graded 6 or harder are given an alphabetical letter, “a,” “b,” or “c.” For further refinement, a “+” is assigned.

Nowadays, the modern French scale for routes runs from 1 to 9c.

Yosemite Decimal System

The YDS was developed by the Sierra Club in Yosemite National Park as a way to categorize technical rock climbs. It was an adaptation of an older grading system that only included steep hiking and scrambling.

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) is a scale of numeric ratings from 5.0 to 5.15, with the lower end of the spectrum representing easier climbs and the upper end of the spectrum representing harder climbs. In the 1960s, the YDS was further specialized by adding letters– climbs rated 5.10 and harder became classified alphabetically with an a, b, c, or d.

5.0-5.4 offers solid handgrips and foot placements.

5.5-5.7 features a bit more slant with generous grips.

5.8 +/- marks the start of true vertical climbs where grips get smaller and trickier.

5.9 +/- introduces routes with some overhangs and tinier grips.

5.10 a, b, c, d are levels where climbers must bring a good deal of skill to manage small holds, bulging sections, and complex moves.

5.11 a, b, c, d demand expertise for steep, taxing climbs that test both power and endurance.

5.12 a, b, c, d challenge climbers with prolonged stretches of technical footwork and clinging to scant holds.

5.13 a, b, c, d; 5.14 a, b, c, d; and 5.15 represent elite climbs, pushing the limits of climbing prowess.

Bouldering Grading Systems

The discipline of bouldering has a grading system that is completely unique from the systems used for route climbing. Similar to the evolution of the route climbing scales, it was the Europeans who designed a bouldering grading system that later inspired how Westerners (most notably Americans) would begin to grade their boulders as well.

Fontainebleu Scale

The Fontainebleau scale, or Font scale, is one of the older rock climbing grading systems for bouldering. It was originally created in the 1960s to begin organizing boulder problems by difficulty in the forests around Fontainebleau, France.

The Font scale is an open-ended scale that ranges from 1 to 9A. From grades 1 through 5, a “+” is attached for further refinement. From grade 6, a capitalized letter “A,” “B,” or “C” can be attached, along with a “+.”

The Font scale for boulders can be distinguished from the French scale for roped routes by the capitalization of the alphabetical value in the grade. In addition, sometimes a “Fb” or capital “F” is used as a prefix.

Font Scale To V Scale Conversions

- 6a to v scale

- 6a+ to v scale

- 6b to v scale

- 6b+ to v scale

- 6c to v scale

- 6c+ to v scale

- 7a to v scale

- 7a+ to v scale

- 7b to v scale

- 7b+ to v scale

- 7c to v scale

- 7c+ to v scale

- 8a to v scale

- 8a+ to v scale

- 8b to v scale

- 8b+ to v scale

- 8c to v scale

- 8c+ to v scale

- 9a to v scale

Fontainebleau’s Circuit Bouldering Grades

The boulder problems in the forests of Fontainebleu are not only graded via the Font Scale. Fontainebleau is unique because it also has circuit grading organized by color.

Circuit grading by color is designed to group boulder problems by approximate difficulty. So, instead of focusing on a specific numerical value from the Font scale, you can pay attention to different a color that is supposed to represent a range of difficulties.

|

Color Circuit |

Grade Range (Font) |

Grade Range (V-Grade) |

|

Yellow |

1A – 3C |

VB – V0 |

|

Orange |

2A – 4B |

VB – V0 |

|

Blue |

3C – 5C |

V0 – V2 |

|

Red |

4C – 6C |

V1 – V4 |

|

Black |

5B – 7A |

V1 – V6 |

|

White |

6B+ – 7C+ |

V4 – V10 |

The Bouldering V Scale

In the 1950s, legendary godfather of American bouldering, John Gill, was grading boulders on a super simple scale ascending from B1 to B3. However, over time, it became clear that Gill’s grading system was incapable of defining accurate grades for the complexity of boulders being climbed.

Eventually, in the 1960s, another iconic American climber, John Sherman, began developing a more nuanced grading system based on his experiences putting up first ascents in Hueco Tanks, Texas.

First popularized due to his local guidebook about Hueco Tanks, Sherman’s grading system became known as the “V Scale” because of his nickname, “the Vermin” or “Verm.” Originally, the V scale was exclusive to Hueco Tanks, but since then, it has become the grading system for bouldering in America.

The modern V scale is a numerical system ranging from easier climbs at V0 to the hardest climbs in the world at V17.

Climbing Grade Conversion Charts

Climbing Grades Compared to Bouldering Grades

The V-scale, used for bouldering, and the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), used for route climbing, represent two distinct grading systems tailored to their specific forms of climbing. Comparing these scales is somewhat akin to comparing sprinting to a marathon; while both are running, the skills and attributes required are quite different. Bouldering grades (V-scale) focus on the difficulty of individual moves or short sequences and are often more dependent on power and technique. In contrast, YDS grades for route climbing consider the hardest section of the climb but also the endurance needed for longer ascents, route-finding, and mental stamina. Therefore, any comparison between the two systems can only offer a rough equivalence, as a boulder problem's intense, short-lived challenge doesn't directly translate to the sustained difficulty found in route climbing. Factors like the length of the climb, type of holds, and steepness all mean that a boulder problem and a route with the same grade may feel very different to climb. Keep this in mind when viewing the grade comparisons listed below—it's the best approximation, but individual experiences will vary.

Keeping it simple, here's how YDS climbing grades and bouldering V-grades roughly match up:

- 5.8 is a V0- on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.9 is a V0 on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.10 is a V0+ on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.11 is a V2-V4 on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.12 is a V4-V7 on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.13 is a V8-V10 on the bouldering V-Scale

- 5.14 is a V11-V14 on the bouldering V-Scale

Other Types of Climbing Grade Scales

The European and American grading systems for bouldering, trad climbing, and sport climbing are the most prominent systems utilized throughout the globe. However, there are a couple of other unique grading systems worth mentioning.

The United Kingdom’s E-Scale

The United Kingdom also has its own grading system for roped climbing. The English Scale, or E-Scale, is configured with Arabic numerals accompanied by letters, just like the French Scale. This portion of the grade represents the technical difficulty of the climb.

However, unique to the E-scale is an additional adjectival or qualitative evaluation that attempts to categorize the physical and psychological difficulty required to climb the route. The modern English adjectival scale ranges from E1 to E11.

For example, a rock climb can be graded 6c to represent the proposed technical difficulty of the climbing and E2 to evaluate the climb in terms of its psychological aspect.

Australian Ewbank Scale

The Australian climbing grade system, also known as the Ewbank System, was invented in the 1960s by an Englishman who emigrated to Australia. It uses a single number to represent the technical difficulty, length, exposure, quality of rock, and protection that contribute to the difficulty of the route.

The modern Ewbank System runs from 1 to 35. For example, an 11 on the Ewbank scale is equivalent to a 2 on the French Scale, while a 35 converts to 9A.

While most popular in Australia, the Ewbank scale is also used in New Zealand and South Africa.

Compared to Climbing Inside, Climbing Outside is “Sandbagged”

Throughout the decades, climbing grades were exclusively created to categorize outdoor routes and boulder problems. However, since the rise in popularity of indoor climbing, many climbers are coming to terms with the disconnect between the grades outside and inside grades.

In general, climbing outside is “sandbagged”– meaning the climbing feels harder than the proposed grade. This is especially true for old-school climbing zones with traditional climbing ethics.

Therefore, outdoor routes graded 5.10a (6a) will feel much harder than indoor routes with the same grade. Outdoor climbing grades are harder (and typically more accurate) because they are steeped in history and culture and have generations worth of refinement (upgrading and downgrading).

On the other hand, indoor climbing grades exist within a vacuum, meaning they are unique to that particular gym and how the small team of routesetters define grades. Routes are changed on a weekly or monthly basis, and therefore, there is no need to rework the grade for long-term viability.

Most importantly, indoor climbing grades tend to be friendlier than outdoor grades because gyms want to facilitate a positive climbing experience so their customers feel motivated to return. In contrast, the rock outside doesn’t give a damn about your ego.

Final Thoughts: Climbing Grading Scales are Subjective

Climbing grades are wildly subjective. Meaning they vary from place to place and over time. Therefore, they should always be taken with a grain of salt and never considered the end all be all.

Yes, it’s nice to track your progress as you get stronger. And yes, it’s convenient to understand what climbs you can or cannot do, especially when traveling around the world or to a new climbing gym. But becoming too obsessed with climbing grades may detract from your overall experience.

Remember–the best climber is not the strongest, they’re the ones having the most fun!